It has been the driest January in 40 years. But January isn’t over, yet.

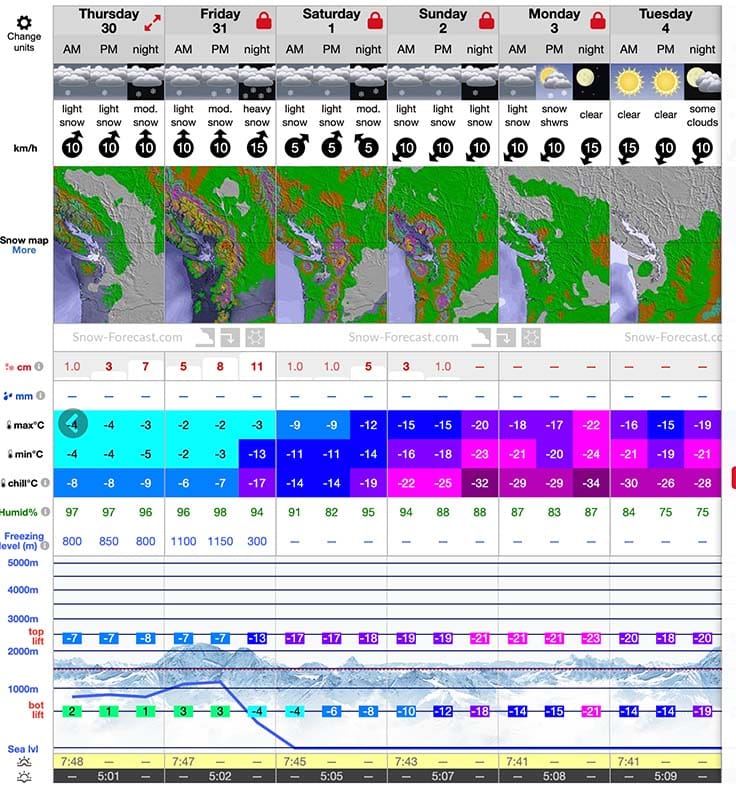

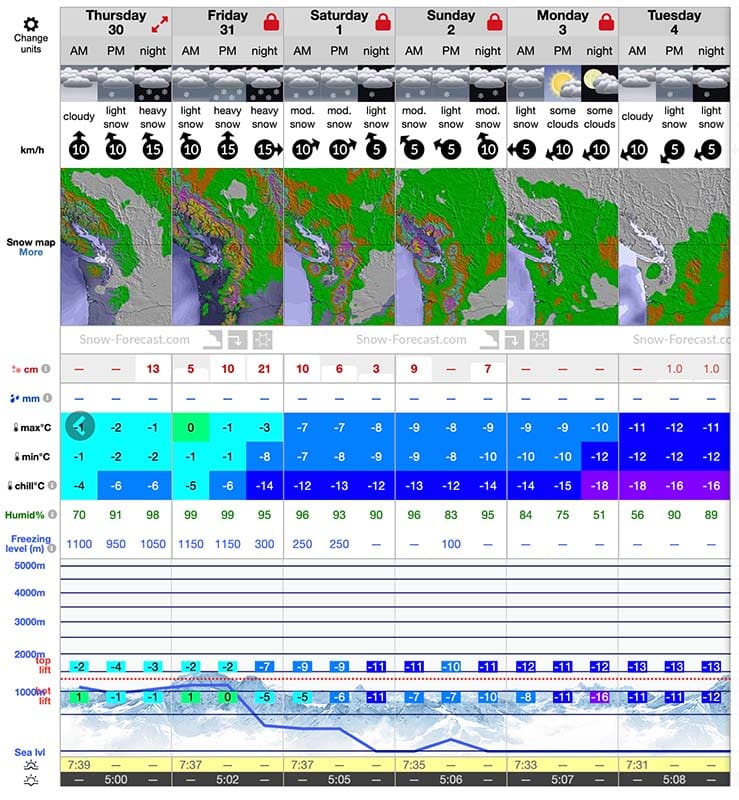

Over the next few days the pattern will finally shift to precipitation, followed by a sudden temperature shift for a cold week ahead. And, depending on when and where you look at a forecast, things seem to be shifting for the storm to come with even more might as it currently builds up some power over the North Pacific.

For skiers and snowboarders, this is music to our ears. It’s been a long dry spell, especially for January. The constant fluctuations have made for a base that is probably rock solid by this point, but thankfully not so much on the surface. Prior to the warm-up earlier this week, the icy conditions and surface hoar would have made for some very unstable conditions this weekend. Thankfully the sun softened it up in most aspects and elevations, with a freezing level of 3400m that is more common in May than the middle of winter. That is a whole other discussion, though.

For now, I’m just psyched to have some snow falling. It really does make for some fun days in life.

What to Look Out For as the Weather Changes

Incoming snow takes a quite low avalanche hazard and will increase exponentially with more snow loading on the top. A common mistake is to take the forecast as gospel and to not pay attention to the actual totals. Even more than just looking at the snow report, you need to get a probe and shovel into the snow. Assumptions are nobody’s friend in the mountains and even a small difference in snow depth can be all the difference, especially if the snow has slab properties.

Beware of What Lies Beneath

Throughout the dry spell we just had, we had a lot of factors that could contribute to a weak layer. The cool, moist air at night was prime conditions for creating surface hoar, a frost that grows and creates a bed surface that is tough for snow to bond to. Surface Hoar can be broken up with wind and warmth, which lowered the probability of that in the alpine where an inversion had warmed up the air quite a bit above freezing. But lower, sheltered elevations didn’t get the same warmth so below treeline might be the most hazardous for surface hoar to have been preserved.

Another factor to look out for is facets, which can come from a big temperature gradient that makes the snow come together and form weak bonds with any snow that falls on top of it. So it will be careful evaluation and a lot of digging in suspect areas to see what lies beneath. If the faceting and/or surface hoar is widespread, it could lead to a persistent weak layer, which will lead to a higher avalanche danger for the rest of the season.

How To Determine if The Snowpack is “Slabby”

The term “slabby” might not have widespread acceptance in the snow science community (at least not officially), but the majority of people out there will know what you mean when you say it. Essentially it’s in the way the snowpack reacts to pressure. Does the snow give way with every flake fending for itself or does it pack together and work as one big cohesive unit? The latter would mean that it has the potential to form a slab on a big slope, which could then lead to a destructive avalanche.

The easiest way to determine the upper snowpack’s properties is to do a quick hand pit. While there is nothing scientific about it, it can still give you a good idea of how the snowpack is behaving at any given moment. This of course does not account for weak layers, and depending on how big of a storm comes in, may not even get below the top layer of storm snow.

How to do a Hand Pit to Assess the Snowpack

The easiest way to quickly see what’s happening in the top of the snowpack is to do a hand pit, also called a hasty pit. In this case you’re just looking to see how the snow is looking en masse, and if it has the potential to form a slap or slip on whatever is beneath.

To make a hand pit you simply dig with your hands (if the snow allows you to) to get down a little bit for easier reading. Then, take a ski pole and carve out a square that is roughly 1foot (30 cm) on all sides. From there, you can try to shear the block by pulling it from the back towards you. If it moves in one big mass, you might have a slab problem around you. If that mass is something you can pick up, even more so. And if that block seems to have effortlessly glided on the surface below it, you have the potential for a big slab avalanche.

Paying Attention to the Wind

Wind is always an important factor when stepping out after a storm. It’s an easy mistake for many to only judge the wind that is currently in front of them, and to forget what the wind was doing while the storm was in full force. This mistake can lead to unfortunate outcomes with powerful lessons on how to always stay attuned to the variables such as wind loading, especially in an Arctic Outflow situation where the wind comes from the opposite direction of the prevailing Southwest, bringing cold air into the canyons and valleys with a bite to it.

This upcoming storm has pretty mellow winds forecasted, which is good news for lowering the hazards when stepping back out into wild terrain. But that’s not to mean that it won’t play a factor. Wind loading will always happen on the lee slide of a slope, just at a more steady pace. Thankfully the bonding should be better than if this were to happen last week before everything warmed up. But as it is now I’d be cautiously optimistic that wind slab properties won’t be unmanageable.

Solar Slopes Will Have Gently Buried Obstacles

One of the biggest hazards in situations like this one is all the hazards that have been exposed by the sun are now covered by a thin layer of fresh snow, which can cause a lot of damage to your skis or board and/or trip you up pretty quickly. Northern aspects are generally less hazardous in comparison because the previous layer didn’t melt away as much. I was in the alpine at Blackcomb earlier this week while it was 6 degrees and you could see numerous hazards all around, with some small enough to disappear pretty quickly in a fresh blanket of snow.

So be sure to take caution and maybe tone down the speed more than you otherwise would if you plan on riding solar aspects this weekend! The temptation is there, just ride with care!

Take photos! Share How it Went!

We are starting up a social network here and would love to see how it went for you. Our goal at Alpine Islands is to make the information exchange much more easy and free between members so that our collective knowledge can elevate. If you’d like to start searching around, you can register and connect with the networks that interest you.